Psychiatric Medication Interaction Checker

Select medications from the dropdown to check for potential interactions. This tool highlights dangerous combinations, evidence-based pairings, and areas requiring clinical review.

When someone is struggling with depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder, doctors often turn to medication to help stabilize their mood, reduce hallucinations, or calm anxiety. But what happens when one pill isn’t enough? In many cases, clinicians add another. And another. And another. This is psychiatric polypharmacy-the use of two or more psychiatric drugs at the same time. It’s become common, but it’s not always safe. In fact, for many patients, especially older adults and those with multiple health conditions, it’s creating more problems than solutions.

Why Do Doctors Prescribe So Many Medications?

It starts with a simple idea: if one antidepressant doesn’t work, try another. If that still doesn’t help, maybe add a mood stabilizer. Or an antipsychotic. Or a sleep aid. For some patients, this approach makes sense. For example, combining a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) like citalopram with bupropion can help people who only partially respond to one drug alone. Adding a short-term benzodiazepine to an antidepressant can ease severe anxiety during the first few weeks of treatment. These are evidence-backed strategies.

But too often, the practice drifts far from evidence. A study of Medicaid enrollees with schizophrenia found that antipsychotic polypharmacy-using two or more antipsychotics at once-jumped from 3.3% in 1999 to 13.7% by 2005. There’s little solid proof this helps. Most of the support comes from case reports, not large, controlled trials. Yet it’s happening. Why? Because clinicians are under pressure. Patients aren’t improving fast enough. Families are worried. Insurance won’t cover therapy. So doctors reach for another pill.

The Hidden Risks of Too Many Pills

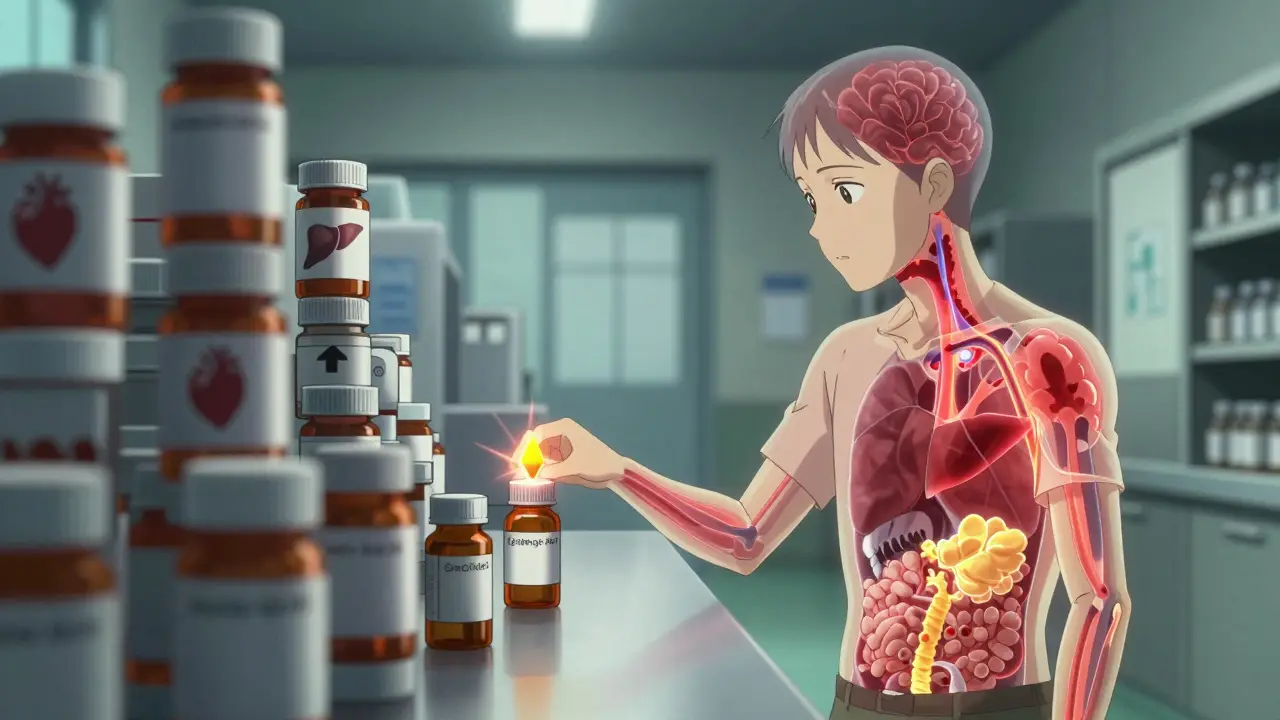

Every medication your body processes puts stress on your liver, kidneys, and brain. When you take five or more drugs at once, those systems get overwhelmed. The CDC found that people taking five or more medications daily-what’s called polypharmacy-had significantly lower physical health scores on quality-of-life measures. Their blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels were harder to control. Their energy dropped. Their balance suffered. Falls increased.

For older adults with schizophrenia, the problem is worse. Many are on antipsychotics for decades, plus medications for diabetes, high blood pressure, arthritis, and heart disease. These drugs can interact in dangerous ways. For example, some antipsychotics slow heart rhythm. If paired with certain antibiotics or antifungals, that effect can become life-threatening. Other combinations cause extreme drowsiness, confusion, or even seizures. The body doesn’t metabolize drugs the same way at 70 as it does at 30. Yet prescriptions often keep piling up without ever being reviewed.

And it’s not just physical. People on multiple psychiatric drugs report feeling foggy, sluggish, emotionally numb. Some stop taking them because they feel worse, not better. But stopping cold turkey can trigger withdrawal or relapse. So they stay on them-sometimes for years-without anyone asking if they’re still needed.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Three groups face the highest danger:

- Older adults with schizophrenia or major depression-often on 8-12 medications total, including non-psychiatric drugs. Their kidneys and liver don’t clear drugs as efficiently, so even normal doses can build up to toxic levels.

- People with multiple chronic illnesses-diabetes, heart disease, COPD, kidney disease. Each condition brings its own meds, and many interact with psychiatric drugs. One study showed multimorbidity was linked to polypharmacy with near-certainty (p < 0.001).

- Patients treated in primary care-not psychiatric clinics. In one study, 37.2% of people getting mental health care in regular doctor’s offices were on complex polypharmacy regimens. These providers rarely specialize in psychopharmacology and may not know the risks of combining certain drugs.

It’s not about the diagnosis. It’s about the number of pills. The more you take, the higher the chance something will go wrong.

What’s Actually Supported by Science?

Not all polypharmacy is bad. Some combinations have strong evidence:

- Antidepressant + bupropion for partial responders to SSRIs

- Antipsychotic + mood stabilizer (like lithium or valproate) for acute mania

- Short-term benzodiazepine + antidepressant for severe anxiety during early treatment

- Antipsychotic + antidepressant for depression with psychotic features

But many others? Not so much. Two antipsychotics together? No major trial proves it works better than one. Antipsychotics with multiple anti-anxiety drugs? Often unnecessary. Antidepressants with stimulants for fatigue? Risky, especially in people with heart conditions.

The American Psychiatric Association says polypharmacy should be a last resort-not a first step. And it should always be reviewed every 3-6 months. But in practice? Many patients go years without a full med review.

Can We Do Better?

Yes. And some places already are.

In Canada and parts of the U.S., Early Psychosis Intervention Programs (EPIP) use strict treatment algorithms. Instead of adding meds blindly, they start with one antipsychotic, monitor closely, and only add others if there’s clear, documented lack of response. In one program, antipsychotic polypharmacy dropped from 483 cases to just 68 after implementing the protocol. Benzodiazepine use also fell. Side effects decreased. Patients felt clearer-headed.

Another breakthrough? Pharmacogenomic testing. This looks at your genes to see how your body breaks down certain drugs. For example, some people have a variant in the CYP2D6 gene that makes them slow metabolizers of many antidepressants and antipsychotics. They get side effects at low doses. Others are ultra-rapid metabolizers-they clear the drug too fast, so it doesn’t work. Testing can cut trial-and-error prescribing by 30-50%. It’s not perfect, but it’s a big step toward personalizing care.

And then there’s deprescribing-the deliberate process of reducing or stopping medications that may no longer be needed or are doing more harm than good. A 2024 study tracked patients over 18 months as their meds were carefully tapered. Results? PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores improved. Blood pressure, HbA1c, and cholesterol dropped. Weight loss occurred. And crucially-relapse rates didn’t spike. Patients didn’t crash. They stabilized.

What Patients and Families Can Do

If you or someone you love is on multiple psychiatric drugs, here’s what to ask:

- Why is each medication here? What symptom is it meant to treat?

- Is there evidence this combination works? Or is it just what’s been done before?

- What happens if we stop one? Is there a plan to taper safely?

- Are we monitoring for side effects? Blood tests? Heart checks? Weight? Movement disorders?

- When’s the next med review? Every six months? Every year? Or never?

Keep a written list of every pill, including doses and why it was prescribed. Bring it to every appointment. Don’t assume your doctor remembers everything. Most don’t.

The Road Ahead

By 2025, over 60% of academic medical centers plan to launch formal deprescribing programs. That’s progress. But right now, 78% of clinics still don’t have a standard protocol for reviewing psychiatric polypharmacy. Clinicians fear destabilizing patients. Patients fear losing the only thing keeping them stable. The system is stuck.

What’s needed isn’t more drugs. It’s better thinking. Better communication. Better tools. We need to stop seeing polypharmacy as a default and start treating it like a high-risk intervention-something that requires informed consent, regular audits, and clear exit plans.

Medication can save lives. But when it’s layered on without purpose, it becomes a burden. And for too many people, that burden is silent-hidden in pill bottles, ignored in chart notes, overlooked in 15-minute appointments. It’s time to change that.

15 Comments

I've seen this play out in my brother's care. He was on six meds for schizophrenia and depression, and honestly? He was a ghost. No spark, no laughter. We pushed for a review, and after cutting two antipsychotics and the benzo, he started recognizing his own face in the mirror again. Not a miracle, but a return to humanity.

This hit me right in the chest. My mom’s been on a cocktail of meds for 12 years-antidepressants, antipsychotics, blood pressure pills, diabetes meds, even a muscle relaxer she doesn’t need anymore. She says she feels like a walking pharmacy. I finally sat down with her doctor last month and asked the five questions from your post. We started tapering one of the antipsychotics slowly. She’s sleeping better. She’s talking to the neighbors again. It’s not about taking less-it’s about taking only what matters. Thank you for saying this out loud.

So we’re just gonna keep throwing drugs at people until they stop screaming or start nodding off? Brilliant. The real mental illness here is the system that thinks 8 pills = treatment. I’ve seen patients on more meds than their grocery list. At least the grocery list has a limit.

The pharmaceutical industry funds 92% of psychiatric research. The FDA approves drugs based on statistical noise, not clinical truth. Polypharmacy isn’t negligence-it’s engineered dependency. They profit from chronicity, not cure. The real scandal isn’t the prescriptions-it’s the silence of the medical elite who benefit from this.

My therapist just dropped a pill I’d been on for 5 years last week. Said she didn’t see any reason for it anymore. I panicked. But after two weeks? I felt lighter. Like I’d been holding my breath. Maybe we’ve been mistaking numbness for stability.

As a clinician in Mumbai, I can confirm this epidemic. Families bring patients with 10+ medications, often prescribed by multiple doctors across different specialties. No coordination. No review. No accountability. We are not treating patients; we are managing pill inventories. The solution requires systemic reform-not individual willpower.

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions inherent in polypharmacy regimens are not merely additive but synergistic in their adverse potential. CYP450 enzyme inhibition, QT prolongation, serotonin syndrome risk-all are exponentially amplified with each additional CNS-active agent. The absence of pharmacogenomic screening constitutes a violation of the standard of care in modern psychopharmacology.

My cousin was on five meds. He stopped one-just one-and cried for three days. Said he felt ‘more himself’ but also ‘more scared.’ That’s the truth no one wants to say: sometimes the pills are the only thing holding the darkness at bay. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to find a better way.

i just want to say thank you for writing this. my sister is on 7 meds and i’ve been too scared to ask if any can come off. but now i’m going to print this out and take it to her next appointment. she deserves to feel alive, not just ‘stable.’

Isn’t it ironic? We’ve mechanized the soul. We reduce existential suffering to a chemical imbalance, then compensate with a pharmacological architecture of dependency. The mind is not a circuit board. But we treat it like one-because it’s easier than sitting with the silence, the grief, the unanswerable questions. Polypharmacy is the opiate of the modern therapeutic class.

Why are we letting foreigners dictate how we treat mental illness? In America, we’ve got the best science, the best labs, the best doctors. But now we’re copying Canada’s ‘de-prescribing’ nonsense? We don’t need less medicine-we need more discipline. And maybe less whining from people who can’t handle a little side effect.

Okay, but what if the real problem isn’t the number of pills-but the fact that we’ve outsourced emotional labor to pharmaceuticals? We don’t teach people how to sit with pain anymore. We just hand them a script. And now we’re shocked when the pills stop working? Maybe the crisis isn’t in the pharmacy-it’s in the culture. We’ve turned healing into a transaction. And like any transaction, when the profit margins drop, we just add another product.

if you’re on more than 3 meds for mental health, you’re not being treated-you’re being managed. and if your doctor hasn’t asked you if you want to be on them in the last year, they’re not your doctor, they’re a pill dispenser. i’m done with this system. i’m done.

I’ve been working with a team that uses pharmacogenomic testing for high-risk polypharmacy cases. One patient, 72, on eight meds including two antipsychotics and a benzo, was identified as a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Her blood levels of quetiapine were 5x the therapeutic range. She was sedated, confused, and falling. We cut the quetiapine and halved the others. Within six weeks, she was gardening again. No relapse. No crashes. Just clarity. This isn’t radical. It’s basic science.

my aunt’s on 11 pills. she can’t walk without a cane. she says she’s ‘fine.’ but she hasn’t laughed in 3 years. i asked the doctor if they could take one away. he said ‘we’ll see.’ we’ve been seeing for 5 years. it’s time to stop seeing and start doing.

Write a comment